-

-

- Observational studies can give us hints

- Never allow yourself to be chilled; dress warmly

- Take regular outdoor exercise, dressed warmly

- If you get a cold, stop exercise, avoid hot (and chilled) drinks

- Stay warm!

-

I’ve been asked for tips for staying healthy during the Covid epidemic. The suggestions below are based on the idea of trying to keep the illness in the nose and throat, and to stop it spreading down to the lungs. In practice, these are my suggestions for avoiding and treating all colds and flu because – in my view – almost all are temperature sensitive. My suggestions aren’t scientifically proven, but they’re based on scientific observations, and they’re almost certainly harmless.

Suggestions:

- Keep warm. Don’t shiver, indoors or outdoors. Don’t stand still outside. If you’re waiting for a bus, walk around. If you get cold, the blood-supply to your nose and throat will decrease very rapidly (this was first shown by two American doctors called Mudd and Grant in 1909) and this seems to interfere with the local immune response.

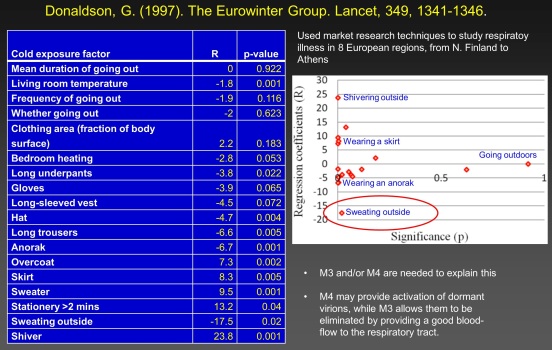

- Clothing matters. Wear a sweater. Wear trousers not a skirt; an anorak, not an overcoat. Wear a hat and gloves in cold weather. All these “personal cold-exposure factors” are correlated with a reduced chance of dying of respiratory illness in Europe.

- Bear in mind that we often carry around populations of dormant viruses, and that these can be activated when we get cold. Viral dormancy has been shown in studies of Antarctic bases in winter, in school-children, in the members of families of people with flu, and in students during the summer holidays.

- Outdoor exercise that causes sweating is protective. Take regular outdoor exercise, but dress up warmly. Be careful for the first few days – bear in mind that you may “wake up” a lot of viruses at once, which could make you sick. Exercise during the day at first, later on in the evening or at night. Don’t get chilled during or after exercise.

- If you get symptoms of a cold or fever stop the exercise! Keep warm but don’t go to an extreme. Try to keep your temperature constant. In particular, don’t allow yourself to become chilled even for a few minutes.

- Keep your feet warm. In 1919 the American doctors Mudd and Grant showed that cooling an individual’s feet rapidly reduced the temperature of their soft palate (presumably by reducing the blood supply, which seems to inhibit the immune response).

- If you notice a cold just beginning, avoid both hot and chilled drinks. Avoid ice-cream too.

- In particular, if you get a sore throat (and this might be my most important tip) avoid the temptation to have a hot drink. Tea and coffee are OK, but they should not be above body temperature. The pain in your throat is a sign that your body is tackling the infection – let it finish the job. Definitely don’t use steam inhalation. Hot drinks etc. will immediately reduce the pain, but it will come back stronger after a few hours – in my experience. (I’m not sure what the explanation is – maybe the heat releases virus particles from cells and spreads them around.)

Scientific sources:

Points 1, 2 and 4 come from an observational study published in The Lancet 1997. They seem to work!

Donaldson G. Cold exposure and winter mortality from ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, respiratory disease, and all causes in warm and cold regions of Europe. The Eurowinter Group. Lancet 1997;349:1341–6. Also see image below.

The other points are based on trial-and-error by myself and my friends over the last six years.

The Hypothesis

For a general discussion of the seasonality of respiratory viruses, written for the layperson, please see

Every winter, colds and flu increase

For detailed scientific information about the seasonality of respiratory viruses, including discussion of the trade-off model, viral dormancy and much else, see my 2016 paper:

For a discussion of the strange timing and duration of influenza epidemics, please see

The strange arrivals – and departures – of influenza epidemics in the UK, 1946-1974

Applications to Covid-19

For information about the probable seasonality of Covid-19, and whether we can expect it to become rarer in the summer, or reappear in the fall, please see

Predicting the seasonality of Covid-19

For comments about the epidemiology of Covid and other respiratory illnesses, please see

Epidemiology of respiratory illness

For discussion of how the trade-off model can be applied to the Covid epidemic see

Covid 19 and the trade-off model

For a simple model of the transmission of viruses such as CoV-2, please see

A simple model of CoV-2 transmission

For comments about how quickly we can expect viruses to adapt to new environments, please see

Adaptability or respiratory viruses

For more detailed scientific points about CoV-2, see

Technical notes on CoV-2 for scientists

One thought on “Suggestions for avoiding respiratory bugs”